The Transformation

How Did We Get Here?

My journey in the conception and beginning of the Real Economist began back in 2006.

I had just taken delivery of Ford F350 pickup truck that had been modified to burn hydrogen gas in its combustion engine. In the bed of the truck, there were three long cylinders full of hydrogen pressurized to 40,000 psi. The truck, which had been modified by North Vancouver engineering firm Sacré-Davey, had two locations that could fuel it: one was just off of the Dollarton Highway in North Vancouver on the banks of Burrard Inlet, and the other was out in Surrey, BC somewhere. (I never made it to that one).

The reason I had been awarded use of this vehicle was because, as a financial journalist of sorts (not technically a journalist because a) I have no education in journalism, and b) I invest in the companies I write about) who was part of a group that was going to raise money to help capitalize on the Hydrogen Highway that was part of Arnold Shwarzenegger’s gubernatorial platform in California.

At the time, we were supposed to be on the brink of getting hydrogen filling stations from Los Angeles to Vancouver. It fizzled out into one of the many false starts to the green economy.

I thought it was going to be no problem to raise millions of dollars for our enterprise, which envisioned capturing hydrogen gas from the manufacturing process of bleach.

But the reality was quite different.

Most Canadian investors were reminded of the debacle of Ballard Energy, which vaporized hundreds of millions of dollars in pursuit of the world’s first commercially produced hydrogen fuel cell. Nobody wanted to touch this deal.

It was at this point that my frustration emerged toward capital markets.

Nobody in the industry was willing to risk money for a good idea: they needed an edge to be induced to play ball, like ultra-cheap founders shares that would guarantee a win as the publicly available shares were sold to the public.

At this point, I was publishing newsletters in the Canadian investment business talking up stocks I thought were good ideas. It always amazed me how poorly capitalized companies were seeing share prices soar while well structured ones routinely were ignored. I realized incrementally that the business was completely rigged and corrupt.

I began to think of things in the context of Real investors versus fake-ass ones who were just there to get rich quick. I began diving into the mechanics and legalities of the rules and regulations governing capital markets in Canada, the US and eventually, around the world.

They all had one thing in common: tacit regulatory support by conflicted government agencies who facilitated what would otherwise be categorized as fraud.

As I traced the corruption up through the food chain by following the money, it soon became apparent that there was collusion if not outright facilitation of predatory strategies by everybody from auditors to courts to the politicians making the rules. And finally I arrived on the doorstep of economists: those largely naive math nerds who were fascinated by the minutiae of transactions, choices, monetary policies, interest rates, capital flows and even a little supply and demand.

Having been an avid reader of economics and political philosophy through literature since I was a kid, I began to see a pattern in the policies of governments and the data they thrust forth as the data-driven justification for decisions affecting resources, taxation, immigration and the electoral processes.

Economists were the little bitches of government who either were oblivious to the fact that they were being subordinated to the interests of government and their billionaire financial underwriters, or were complicit.

Either way, it became tremendously obvious that the Canadian government’s insistence on the economics justifying the toxification of northern Alberta’s rivers and streams were created by economists.

The hydrogen highway was never going to be a reality until the interests of the elite financial groups who drive government policy decided there was no more upside in the legacy hydrocarbon business, which in Canada, was freshly important since the discover of the oil sands.

Now, Canada’s banking cartel and the Canadian government are so heavily invested in oil sands and natural gas export infrastructure that they cannot afford to admit the economics don’t make sense because it would cause too much damage to their balance sheets. So economists must keep on justifying oil sands and natgas investment so that the whole country doesn’t mutiny.

Fortunately for them, there is enough of a tradition of employment in hydrocarbon energy that they have been able to create the reality of public support because none of those good old boys can see over the hood ornament of their Dodge Rams to see that there are other professions after oil and gas.

But now I have descended into rant mode, so I will leave it there.

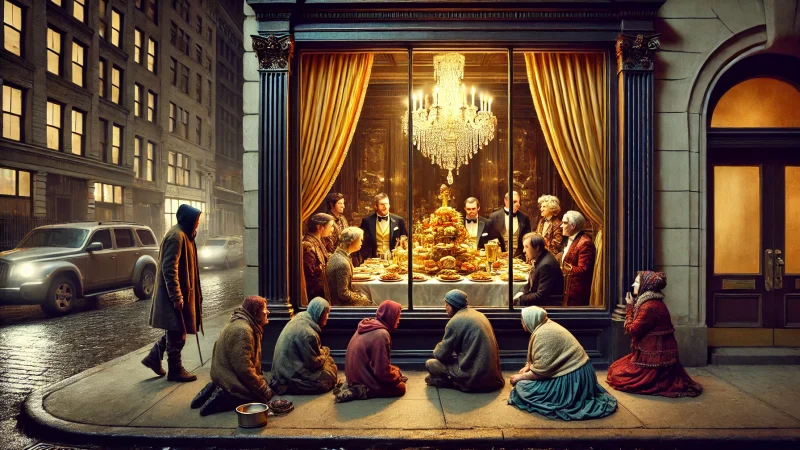

Bottom line is the hypocrisy of global governance and industrial leadership coupled with a CAPITALIST driven appreciation for the basic concept that the health of global enterprise in the long term is directly correlated to the health of the global ecology. In the long run.

Man, 886win is alright! Been playing for a bit and I’m digging the vibe. They’ve got a good selection of games. Give ’em a try at 886win and see what you think.

Yo, heard about iwin68club? Gave it a spin and gotta say, not bad at all. Smooth interface and some decent games. Might be my new go-to. Check it out at iwin68club.

8win55vip, sounds exclusive! I’m hoping for some serious perks and top-notch service if I’m playing VIP. Show me the winning and the rewards! 8win55vip

Yo, check out c77bet! Been playing there for a bit now. It’s got a decent selection of games and the payouts are pretty quick. Definitely worth a look if you’re looking for a new spot to gamble. Get your game on at c77bet!

6wgamepk is my go-to place for playing games online. It’s not going to break the bank, but it is good fun! Good for a quick burst of fun! 6wgamepk

Just stumbled upon 92strikegame and it’s got some interesting options. Gameplay’s a little different, but that’s what makes it fun! Worth a try 92strikegame.

Alright betbet, let’s get betting! Hoping for some big wins this time. Time to risk it for the biscuit: betbet

Just a heads-up! winbuzzregistration made the whole signing-up thing a piece of cake. Account’s all set, and I’m ready to roll. Definitely check it out if you haven’t registered yet!

jljl88com, eh? Gave it a shot the other day. Seems legit, navigation is pretty smooth and I like what I saw. Could use a bit more polish, but honestly, not bad! Worth a peek: jljl88com